Translating Shakespeare in South Africa

South Africa has 12 official languages (including SA Sign Language) and is a richly multilingual country. So why do we still think that Shakespeare has to be read or performed in English?

(For a fun reminder of the relationship between Shakespeare’s work and the English language, watch this or this ... But don’t forget that Shakespeare’s presence, in English, in South Africa, is part of a global story about British imperialism and its legacies, one aspect of which is the dominance of English as a world language.)

In this section of Shakespeare ZA, you can read about the history of translating Shakespeare into South African languages (below) and explore a rich collection of digitised play texts in Setswana, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Afrikaans, Sepedi, Xitsonga, Tshivenda and Sesotho!

You can also learn more about condensed translations and adaptations of numerous plays for performance by high school learners, available from the Shakespeare Schools Festival (SA), in our Partnerships section.

A bit of history

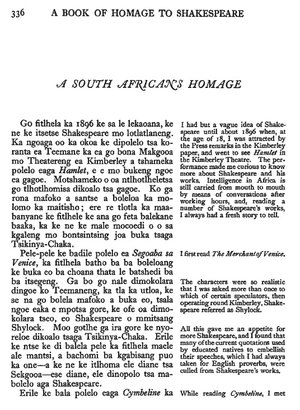

The first formal translation of Shakespeare’s work into a South African language was undertaken by Solomon T. Plaatje, one of the most important figures in the country’s political, cultural and literary history. Plaatje was a founding member of the South African Native National Congress (later the ANC) and travelled to Britain around the time of the First World War to seek support for his campaign against racist oppression in what was then the Union of South Africa. While in the UK, he was asked to make a bilingual English-Setswana contribution to the international Book of Homage to Shakespeare published in 1916.

Portrait of Sol Plaatje during his 1916 trip to England.

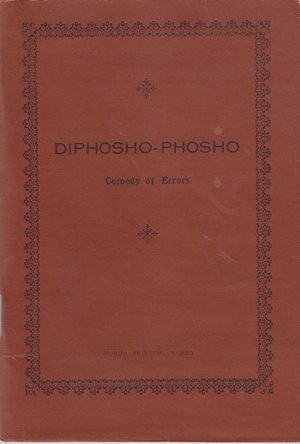

Plaatje went on to translate six of Shakespeare’s plays into his mother tongue: Diphosho-phosho (The Comedy of Errors), Mashoabi-shoabi (The Merchant of Venice), Matsepa-tsapa a Lefeala (Much Ado about Nothing), Dintshontsho tsa bo-Juliuse Kesara (Julius Caesar), Othello and Romeo and Juliet (for which he did not provide a Setswana title). Sadly, only two of these were subsequently published: Diphosho-phosho (1930) and Dintshontsho tsa bo-Juliuse Kesara (1937).

A number of translators have followed in Plaatje’s footsteps, but only a handful of these texts are readily available and accessible. A full bibliography of translations into South African languages was last produced in 1988! One of Shakespeare ZA’s ongoing projects is to update this bibliography and to digitise as many translations as possible.

The actor John Kani recounts how, after discovering B.B. Mdledle’s isiXhosa version of Julius Caesar as a high school student in the 1950s, he found the experience of reading Shakespeare’s text disappointing: “I felt that Shakespeare had failed to capture the beauty of Mdledle’s writing!” Another significant Shakespearean transition from English to isiXhosa was R.L. Peteni’s novel Hill of Fools / Kwazidenge (1976/1980), based on Romeo and Juliet. (For more on the fascinating history of this book, take a look at some of the articles in this special issue of the journal English in Africa.)

Probably the most famous isiZulu version of Shakespeare is Welcome Msomi’s 1970 play Umabatha (Macbeth) – read more about it here. This was more of a “cultural adaptation” than a direct translation, although there are various examples of Shakespeare’s playtexts translated into isiZulu.

Over the second half of the twentieth century, a number of celebrated Afrikaans writers – particularly poets – translated Shakespeare’s work. Prominent examples are Uys Krige’s Twaalfde Nag (Twelfth Night, 1967), Breyten Breytenbach’s Titus Andronicus (1970) and Andre Brink’s various translations. Perhaps the most prolific translator of Shakespeare into Afrikaans was Eitemal: Macbeth (1965), Hamlet (1973), Midsomernagdroom (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1975) and Die Wintersprokie (The Winter’s Tale, 1975). A few years ago a production of Macbeth directed by Marthinus Basson revived Eitemal’s translation.

In 2000, Yael Farber’s SeZaR! combined Shakespeare’s Elizabethan English with isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho and Setswana. The Isango Ensemble performed a multilingual adaptation of the narrative poem Venus and Adonis as part of the Globe to Globe Festival in London in 2012. uVenas no Adonisi included isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho, Setswana, Afrikaans and English. (Read more about it here.)

More recent theatrical experiments in Shakespearean translanguaging on South African stages range from Umsebenzi Ka Bra Shakes (2019) to DNA’s Macbeth (2021). Exciting multilingual film projects include the JAM ensemble’s JAM at the Windybrow and A Midsummer Ice Cream, and CineSouth Studios’ pioneering web platform and work-in-progress documentary feature, Speak Me A Speech.