“Nothing That Is So, Is So”: Jazz, Gender and La Dolce Vita as Maynardville turns 70

Zainab Gaffoor

Under the intoxicating fairy lights and the stars of the night sky, the Maynardville Open-Air Theatre celebrates its seventieth anniversary season with a production of Twelfth Night. Director Steven Stead’s fictional kingdom of Illyria is not a distant, mythical land of antiquity but a vivid sensory invocation of 1960s Fellini-esque Italy.

In a world of high fashion, cocktails and jazz music, a Dolce Vita aesthetic drips with the glamour of the silver screen. By transporting Shakespeare’s melancholic comedy to an era obsessed with image, celebrity and the surface, Stead illuminates the play’s central preoccupation: the friction between the curated self and the messy, authentic human beneath.

The production does not fight the outdoor elements; it embraces them. Greg King’s set design acts as an extension of the park, allowing the rustling trees and the skies above to serve as the natural backdrop for this fantasy. The wind rattles through the Maynardville trees, evoking our own storms of the Cape. The Sea Captain (Paul Savage) enters speaking in a recognisable Capetonian manner, a local guide in Illyria, bringing Viola and the audience out of the mythical sea and welcoming us onto familiar shores. While this is a neat touch, it is a solitary anchor for a production that otherwise drifts resolutely towards Europe. For Maynardville’s seventieth anniversary season, one might have expected a more rigorous grounding in the South African context, or perhaps even in the Global South more broadly. By holding back on integrating more local textures, this Twelfth Night misses the chance to truly claim Illyria for a South African audience.

The production’s intellectual and creative weight, however, lies in its exploration of identity and performance. At the centre of this is Emily Child’s portrayal of Viola. As Viola impersonating a male youth, Cesario, Child’s performance of masculinity is not an attempt to be a convincing man, but rather a convincing schoolboy: adopting a humorous widened gait and a stiff chest-forward posture with legs spread apart and hands in pockets. Child makes us aware of the labour Viola undertakes to maintain the façade.

Emily Child as Viola (photo: Claude Barnardo)

The directorial focus on the fragility of gender performance allows for a much-appreciated queering of the central love triangle, which feels both radical and textually supported. The chemistry between Cesario and Orsino is palpable, culminating in a moment (which drew audible gasps from some in the opening night audience) when Orsino kisses ‘Cesario’ while Viola is still presenting as a man. By having Orsino act on his desire for the person rather than the gender, this production validates the queer undertones of the text. It reveals that Orsino’s love is a genuine connection that transcends the binary.

While the production radically interrogates gender and sexuality, its approach to casting feels less adventurous. The casting is diverse, yet the distribution of roles suggests a lack of attention to racial dynamics. Talented actors of colour such as Ntlanthla Morgan Kutu (Antonio/Curio), Lungile Lallie (Fabian/Valentine) and Savage (Sea Captain/Office/Priest) deliver compelling performances in a variety of minor roles, yet they remain on the periphery just as their characters are lower in Illyria’s social hierarchy. In a production that works so hard to subvert the traditional gender binaries, the seats of power and romance within the play are occupied exclusively by white bodies. If the 1960s was a space of exclusion, a contemporary South African production has the opportunity to subvert that history rather than replicate it. A more representative casting of the central characters would have added a layer of richness for the South African audience.

Michael Richard as Sir Toby Belch, Natasha Sutherland as Maria, Aidan Scott as Sir Andrew Aguecheek and Lungile Lallie as Fabian (photo: Claude Barnardo)

Jenny Stead’s Olivia is dressed in the height of 1960s couture, treating her mourning as a fashion statement. Her “veil” being a pair of designer sunglasses is a clever choice by costume designer Maritha Visagie. This brilliant modernisation of the trope of the unapproachable lady frames Olivia not as a recluse but as something like a celebrity hiding from paparazzi. Her infatuation with Cesario is played with a frantic, breathless energy that exposes the cracks in her composed exterior. When she yearns for our schoolboy, the comedy comes not from her foolishness, but from the collapse of her carefully constructed cool.

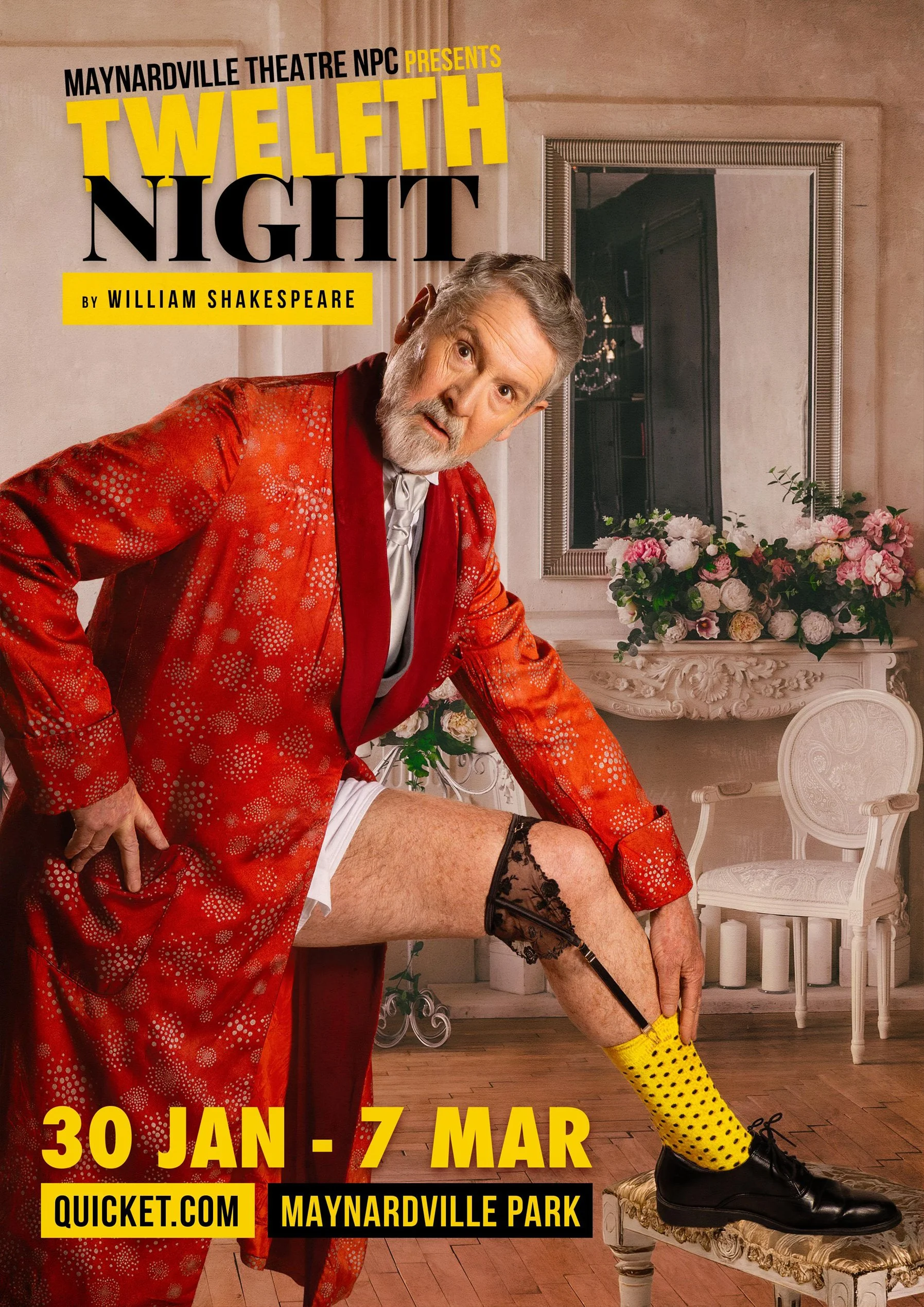

Equally compelling is Graham Hopkins as Malvolio, playing the uptight, class-obsessed, buzzkilling bureaucrat. Given the sleek, high-fashion aesthetic of the play, the production handles Malvolio’s sartorial humiliation with visual wit. In a world of black and white, his sudden appearance in neon-yellow stockings is all the more visually assaulting, with the garter truly selling the absurdity. Hopkins plays the moment with a deluded confidence that makes Malvolio’s humiliation sting even more.

Jenny Stead as Viola (photo: Claude Barnardo)

The physical comedy of the play reaches its zenith in the duel between Sir Andrew Aguecheek (a passionately silly Aidan Scott) and Cesario. Stead opts to replace the traditional swords with boxing gloves, a choice that fundamentally alters the stakes of the scene by transforming the lethal encounter into a clumsy, sporting farce. The fight choreography is deliberately inept, highlighting a meta-theatrical layer of performance within a performance – we watch Scott playing Sir Andrew, trying to play a tough guy, and Child playing Viola, playing Cesario, trying to play a brave man. The actors lean into the physical comedy, flailing and circling in a way that exposes their characters’ lack of aggression.

The true soul of this production belongs to David Viviers as Feste, the Fool. Viviers discards the traditional cap-and-bells for a sleek suit and a cigarette, opening the show seated at a piano like a lounge singer in a smoky bar. He is the MVP, the wittiest and most perceptive character of all, seeing through everyone’s appearances. Wessel Odendaal’s jazz scores act as their own character, stitching together scenes and being present as the emotional conductor, with Viviers being the vessel. When Viviers sings, the glamour of the setting fades, revealing the reality beneath the façade. In a world where everyone is performing a role, the fool is the only one telling the truth.

David Viviers as Feste (photo: Claude Barnardo)

The tension throughout the play is resolved in the production’s closing moments. Stead opts for a finale of unadulterated warmth – invoking the tradition of the concluding ‘jig’ in the form of a wholesome, collective dance sequence that serves as the wedding celebration for the three central couples: Orsino and Viola, Olivia and Sebastian, and the unexpectedly delightful pairing of Maria and Sir Toby.

Watching the entire cast move together is a restorative experience. It is a moment of joy that washes away the bitterness of the earlier conflicts, allowing the audience to leave the park feeling that, for these characters at least, La Dolce Vita has finally become a reality.